Note

Documentation for the deprecated @st.cache decorator can be found in Optimize performance with st.cache.

Caching overview

Streamlit runs your script from top to bottom at every user interaction or code change. This execution model makes development super easy. But it comes with two major challenges:

- Long-running functions run again and again, which slows down your app.

- Objects get recreated again and again, which makes it hard to persist them across reruns or sessions.

But don't worry! Streamlit lets you tackle both issues with its built-in caching mechanism. Caching stores the results of slow function calls, so they only need to run once. This makes your app much faster and helps with persisting objects across reruns. Cached values are available to all users of your app. If you need to save results that should only be accessible within a session, use Session State instead.

Minimal example

To cache a function in Streamlit, you must decorate it with one of two decorators (st.cache_data or st.cache_resource):

@st.cache_data

def long_running_function(param1, param2):

return …

In this example, decorating long_running_function with @st.cache_data tells Streamlit that whenever the function is called, it checks two things:

- The values of the input parameters (in this case,

param1andparam2). - The code inside the function.

If this is the first time Streamlit sees these parameter values and function code, it runs the function and stores the return value in a cache. The next time the function is called with the same parameters and code (e.g., when a user interacts with the app), Streamlit will skip executing the function altogether and return the cached value instead. During development, the cache updates automatically as the function code changes, ensuring that the latest changes are reflected in the cache.

As mentioned, there are two caching decorators:

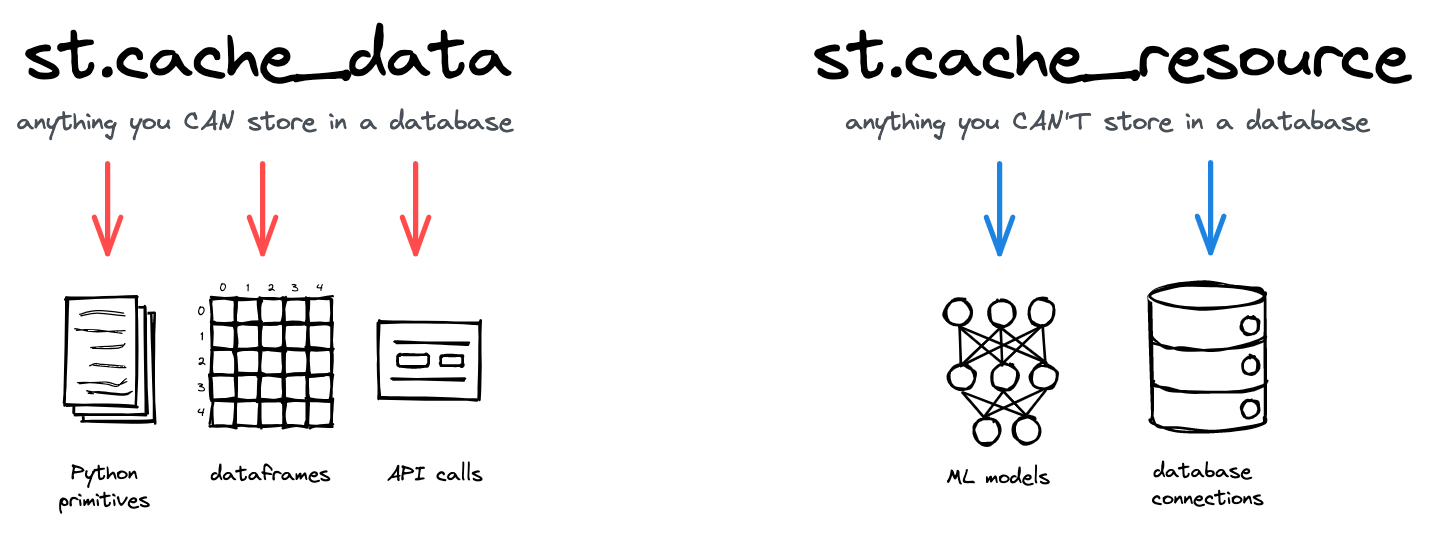

st.cache_datais the recommended way to cache computations that return data: loading a DataFrame from CSV, transforming a NumPy array, querying an API, or any other function that returns a serializable data object (str, int, float, DataFrame, array, list, …). It creates a new copy of the data at each function call, making it safe against mutations and race conditions. The behavior ofst.cache_datais what you want in most cases – so if you're unsure, start withst.cache_dataand see if it works!st.cache_resourceis the recommended way to cache global resources like ML models or database connections – unserializable objects that you don't want to load multiple times. Using it, you can share these resources across all reruns and sessions of an app without copying or duplication. Note that any mutations to the cached return value directly mutate the object in the cache (more details below).

Streamlit's two caching decorators and their use cases.

Basic usage

st.cache_data

st.cache_data is your go-to command for all functions that return data – whether DataFrames, NumPy arrays, str, int, float, or other serializable types. It's the right command for almost all use cases! Within each user session, an @st.cache_data-decorated function returns a copy of the cached return value (if the value is already cached).

Usage

Let's look at an example of using st.cache_data. Suppose your app loads the Uber ride-sharing dataset – a CSV file of 50 MB – from the internet into a DataFrame:

def load_data(url):

df = pd.read_csv(url) # 👈 Download the data

return df

df = load_data("https://github.com/plotly/datasets/raw/master/uber-rides-data1.csv")

st.dataframe(df)

st.button("Rerun")

Running the load_data function takes 2 to 30 seconds, depending on your internet connection. (Tip: if you are on a slow connection, use this 5 MB dataset instead). Without caching, the download is rerun each time the app is loaded or with user interaction. Try it yourself by clicking the button we added! Not a great experience… 😕

Now let's add the @st.cache_data decorator on load_data:

@st.cache_data # 👈 Add the caching decorator

def load_data(url):

df = pd.read_csv(url)

return df

df = load_data("https://github.com/plotly/datasets/raw/master/uber-rides-data1.csv")

st.dataframe(df)

st.button("Rerun")

Run the app again. You'll notice that the slow download only happens on the first run. Every subsequent rerun should be almost instant! 💨

Behavior

How does this work? Let's go through the behavior of st.cache_data step by step:

- On the first run, Streamlit recognizes that it has never called the

load_datafunction with the specified parameter value (the URL of the CSV file) So it runs the function and downloads the data. - Now our caching mechanism becomes active: the returned DataFrame is serialized (converted to bytes) via pickle and stored in the cache (together with the value of the

urlparameter). - On the next run, Streamlit checks the cache for an entry of

load_datawith the specificurl. There is one! So it retrieves the cached object, deserializes it to a DataFrame, and returns it instead of re-running the function and downloading the data again.

This process of serializing and deserializing the cached object creates a copy of our original DataFrame. While this copying behavior may seem unnecessary, it's what we want when caching data objects since it effectively prevents mutation and concurrency issues. Read the section “Mutation and concurrency issues" below to understand this in more detail.

Warning

st.cache_data implicitly uses the pickle module, which is known to be insecure. Anything your cached function returns is pickled and stored, then unpickled on retrieval. Ensure your cached functions return trusted values because it is possible to construct malicious pickle data that will execute arbitrary code during unpickling. Never load data that could have come from an untrusted source in an unsafe mode or that could have been tampered with. Only load data you trust.

Examples

DataFrame transformations

In the example above, we already showed how to cache loading a DataFrame. It can also be useful to cache DataFrame transformations such as df.filter, df.apply, or df.sort_values. Especially with large DataFrames, these operations can be slow.

@st.cache_data

def transform(df):

df = df.filter(items=['one', 'three'])

df = df.apply(np.sum, axis=0)

return df

Array computations

Similarly, it can make sense to cache computations on NumPy arrays:

@st.cache_data

def add(arr1, arr2):

return arr1 + arr2

Database queries

You usually make SQL queries to load data into your app when working with databases. Repeatedly running these queries can be slow, cost money, and degrade the performance of your database. We strongly recommend caching any database queries in your app. See also our guides on connecting Streamlit to different databases for in-depth examples.

connection = database.connect()

@st.cache_data

def query():

return pd.read_sql_query("SELECT * from table", connection)

Tip

You should set a ttl (time to live) to get new results from your database. If you set st.cache_data(ttl=3600), Streamlit invalidates any cached values after 1 hour (3600 seconds) and runs the cached function again. See details in Controlling cache size and duration.

API calls

Similarly, it makes sense to cache API calls. Doing so also avoids rate limits.

@st.cache_data

def api_call():

response = requests.get('https://jsonplaceholder.typicode.com/posts/1')

return response.json()

Running ML models (inference)

Running complex machine learning models can use significant time and memory. To avoid rerunning the same computations over and over, use caching.

@st.cache_data

def run_model(inputs):

return model(inputs)

st.cache_resource

st.cache_resource is the right command to cache “resources" that should be available globally across all users, sessions, and reruns. It has more limited use cases than st.cache_data, especially for caching database connections and ML models. Within each user session, an @st.cache_resource-decorated function returns the cached instance of the return value (if the value is already cached). Therefore, objects cached by st.cache_resource act like singletons and can mutate.

Usage

As an example for st.cache_resource, let's look at a typical machine learning app. As a first step, we need to load an ML model. We do this with Hugging Face's transformers library:

from transformers import pipeline

model = pipeline("sentiment-analysis") # 👈 Load the model

If we put this code into a Streamlit app directly, the app will load the model at each rerun or user interaction. Repeatedly loading the model poses two problems:

- Loading the model takes time and slows down the app.

- Each session loads the model from scratch, which takes up a huge amount of memory.

Instead, it would make much more sense to load the model once and use that same object across all users and sessions. That's exactly the use case for st.cache_resource! Let's add it to our app and process some text the user entered:

from transformers import pipeline

@st.cache_resource # 👈 Add the caching decorator

def load_model():

return pipeline("sentiment-analysis")

model = load_model()

query = st.text_input("Your query", value="I love Streamlit! 🎈")

if query:

result = model(query)[0] # 👈 Classify the query text

st.write(result)

If you run this app, you'll see that the app calls load_model only once – right when the app starts. Subsequent runs will reuse that same model stored in the cache, saving time and memory!

Behavior

Using st.cache_resource is very similar to using st.cache_data. But there are a few important differences in behavior:

-

st.cache_resourcedoes not create a copy of the cached return value but instead stores the object itself in the cache. All mutations on the function's return value directly affect the object in the cache, so you must ensure that mutations from multiple sessions do not cause problems. In short, the return value must be thread-safe.priority_high Warning

Using

st.cache_resourceon objects that are not thread-safe might lead to crashes or corrupted data. Learn more below under Mutation and concurrency issues. -

Not creating a copy means there's just one global instance of the cached return object, which saves memory, e.g. when using a large ML model. In computer science terms, we create a singleton.

-

Return values of functions do not need to be serializable. This behavior is great for types not serializable by nature, e.g., database connections, file handles, or threads. Caching these objects with

st.cache_datais not possible.

Examples

Database connections

st.cache_resource is useful for connecting to databases. Usually, you're creating a connection object that you want to reuse globally for every query. Creating a new connection object at each run would be inefficient and might lead to connection errors. That's exactly what st.cache_resource can do, e.g., for a Postgres database:

@st.cache_resource

def init_connection():

host = "hh-pgsql-public.ebi.ac.uk"

database = "pfmegrnargs"

user = "reader"

password = "NWDMCE5xdipIjRrp"

return psycopg2.connect(host=host, database=database, user=user, password=password)

conn = init_connection()

Of course, you can do the same for any other database. Have a look at our guides on how to connect Streamlit to databases for in-depth examples.

Loading ML models

Your app should always cache ML models, so they are not loaded into memory again for every new session. See the example above for how this works with 🤗 Hugging Face models. You can do the same thing for PyTorch, TensorFlow, etc. Here's an example for PyTorch:

@st.cache_resource

def load_model():

model = torchvision.models.resnet50(weights=ResNet50_Weights.DEFAULT)

model.eval()

return model

model = load_model()

Deciding which caching decorator to use

The sections above showed many common examples for each caching decorator. But there are edge cases for which it's less trivial to decide which caching decorator to use. Eventually, it all comes down to the difference between “data" and “resource":

- Data are serializable objects (objects that can be converted to bytes via pickle) that you could easily save to disk. Imagine all the types you would usually store in a database or on a file system – basic types like str, int, and float, but also arrays, DataFrames, images, or combinations of these types (lists, tuples, dicts, and so on).

- Resources are unserializable objects that you usually would not save to disk or a database. They are often more complex, non-permanent objects like database connections, ML models, file handles, threads, etc.

From the types listed above, it should be obvious that most objects in Python are “data." That's also why st.cache_data is the correct command for almost all use cases. st.cache_resource is a more exotic command that you should only use in specific situations.

Or if you're lazy and don't want to think too much, look up your use case or return type in the table below 😉:

| Use case | Typical return types | Caching decorator |

|---|---|---|

| Reading a CSV file with pd.read_csv | pandas.DataFrame | st.cache_data |

| Reading a text file | str, list of str | st.cache_data |

| Transforming pandas dataframes | pandas.DataFrame, pandas.Series | st.cache_data |

| Computing with numpy arrays | numpy.ndarray | st.cache_data |

| Simple computations with basic types | str, int, float, … | st.cache_data |

| Querying a database | pandas.DataFrame | st.cache_data |

| Querying an API | pandas.DataFrame, str, dict | st.cache_data |

| Running an ML model (inference) | pandas.DataFrame, str, int, dict, list | st.cache_data |

| Creating or processing images | PIL.Image.Image, numpy.ndarray | st.cache_data |

| Creating charts | matplotlib.figure.Figure, plotly.graph_objects.Figure, altair.Chart | st.cache_data (but some libraries require st.cache_resource, since the chart object is not serializable – make sure not to mutate the chart after creation!) |

| Loading ML models | transformers.Pipeline, torch.nn.Module, tensorflow.keras.Model | st.cache_resource |

| Initializing database connections | pyodbc.Connection, sqlalchemy.engine.base.Engine, psycopg2.connection, mysql.connector.MySQLConnection, sqlite3.Connection | st.cache_resource |

| Opening persistent file handles | _io.TextIOWrapper | st.cache_resource |

| Opening persistent threads | threading.thread | st.cache_resource |

Advanced usage

Controlling cache size and duration

If your app runs for a long time and constantly caches functions, you might run into two problems:

- The app runs out of memory because the cache is too large.

- Objects in the cache become stale, e.g. because you cached old data from a database.

You can combat these problems with the ttl and max_entries parameters, which are available for both caching decorators.

The ttl (time-to-live) parameter

ttl sets a time to live on a cached function. If that time is up and you call the function again, the app will discard any old, cached values, and the function will be rerun. The newly computed value will then be stored in the cache. This behavior is useful for preventing stale data (problem 2) and the cache from growing too large (problem 1). Especially when pulling data from a database or API, you should always set a ttl so you are not using old data. Here's an example:

@st.cache_data(ttl=3600) # 👈 Cache data for 1 hour (=3600 seconds)

def get_api_data():

data = api.get(...)

return data

Tip

You can also set ttl values using timedelta, e.g., ttl=datetime.timedelta(hours=1).

The max_entries parameter

max_entries sets the maximum number of entries in the cache. An upper bound on the number of cache entries is useful for limiting memory (problem 1), especially when caching large objects. The oldest entry will be removed when a new entry is added to a full cache. Here's an example:

@st.cache_data(max_entries=1000) # 👈 Maximum 1000 entries in the cache

def get_large_array(seed):

np.random.seed(seed)

arr = np.random.rand(100000)

return arr

Customizing the spinner

By default, Streamlit shows a small loading spinner in the app when a cached function is running. You can modify it easily with the show_spinner parameter, which is available for both caching decorators:

@st.cache_data(show_spinner=False) # 👈 Disable the spinner

def get_api_data():

data = api.get(...)

return data

@st.cache_data(show_spinner="Fetching data from API...") # 👈 Use custom text for spinner

def get_api_data():

data = api.get(...)

return data

Excluding input parameters

In a cached function, all input parameters must be hashable. Let's quickly explain why and what it means. When the function is called, Streamlit looks at its parameter values to determine if it was cached before. Therefore, it needs a reliable way to compare the parameter values across function calls. Trivial for a string or int – but complex for arbitrary objects! Streamlit uses hashing to solve that. It converts the parameter to a stable key and stores that key. At the next function call, it hashes the parameter again and compares it with the stored hash key.

Unfortunately, not all parameters are hashable! E.g., you might pass an unhashable database connection or ML model to your cached function. In this case, you can exclude input parameters from caching. Simply prepend the parameter name with an underscore (e.g., _param1), and it will not be used for caching. Even if it changes, Streamlit will return a cached result if all the other parameters match up.

Here's an example:

@st.cache_data

def fetch_data(_db_connection, num_rows): # 👈 Don't hash _db_connection

data = _db_connection.fetch(num_rows)

return data

connection = init_connection()

fetch_data(connection, 10)

But what if you want to cache a function that takes an unhashable parameter? For example, you might want to cache a function that takes an ML model as input and returns the layer names of that model. Since the model is the only input parameter, you cannot exclude it from caching. In this case you can use the hash_funcs parameter to specify a custom hashing function for the model.

The hash_funcs parameter

As described above, Streamlit's caching decorators hash the input parameters and cached function's signature to determine whether the function has been run before and has a return value stored ("cache hit") or needs to be run ("cache miss"). Input parameters that are not hashable by Streamlit's hashing implementation can be ignored by prepending an underscore to their name. But there two rare cases where this is undesirable. i.e. where you want to hash the parameter that Streamlit is unable to hash:

- When Streamlit's hashing mechanism fails to hash a parameter, resulting in a

UnhashableParamErrorbeing raised. - When you want to override Streamlit's default hashing mechanism for a parameter.

Let's discuss each of these cases in turn with examples.

Example 1: Hashing a custom class

Streamlit does not know how to hash custom classes. If you pass a custom class to a cached function, Streamlit will raise a UnhashableParamError. For example, let's define a custom class MyCustomClass that accepts an initial integer score. Let's also define a cached function multiply_score that multiplies the score by a multiplier:

import streamlit as st

class MyCustomClass:

def __init__(self, initial_score: int):

self.my_score = initial_score

@st.cache_data

def multiply_score(obj: MyCustomClass, multiplier: int) -> int:

return obj.my_score * multiplier

initial_score = st.number_input("Enter initial score", value=15)

score = MyCustomClass(initial_score)

multiplier = 2

st.write(multiply_score(score, multiplier))

If you run this app, you'll see that Streamlit raises a UnhashableParamError since it does not know how to hash MyCustomClass:

UnhashableParamError: Cannot hash argument 'obj' (of type __main__.MyCustomClass) in 'multiply_score'.

To fix this, we can use the hash_funcs parameter to tell Streamlit how to hash MyCustomClass. We do this by passing a dictionary to hash_funcs that maps the name of the parameter to a hash function. The choice of hash function is up to the developer. In this case, let's define a custom hash function hash_func that takes the custom class as input and returns the score. We want the score to be the unique identifier of the object, so we can use it to deterministically hash the object:

import streamlit as st

class MyCustomClass:

def __init__(self, initial_score: int):

self.my_score = initial_score

def hash_func(obj: MyCustomClass) -> int:

return obj.my_score # or any other value that uniquely identifies the object

@st.cache_data(hash_funcs={MyCustomClass: hash_func})

def multiply_score(obj: MyCustomClass, multiplier: int) -> int:

return obj.my_score * multiplier

initial_score = st.number_input("Enter initial score", value=15)

score = MyCustomClass(initial_score)

multiplier = 2

st.write(multiply_score(score, multiplier))

Now if you run the app, you'll see that Streamlit no longer raises a UnhashableParamError and the app runs as expected.

Let's now consider the case where multiply_score is an attribute of MyCustomClass and we want to hash the entire object:

import streamlit as st

class MyCustomClass:

def __init__(self, initial_score: int):

self.my_score = initial_score

@st.cache_data

def multiply_score(self, multiplier: int) -> int:

return self.my_score * multiplier

initial_score = st.number_input("Enter initial score", value=15)

score = MyCustomClass(initial_score)

multiplier = 2

st.write(score.multiply_score(multiplier))

If you run this app, you'll see that Streamlit raises a UnhashableParamError since it cannot hash the argument 'self' (of type __main__.MyCustomClass) in 'multiply_score'. A simple fix here could be to use Python's hash() function to hash the object:

import streamlit as st

class MyCustomClass:

def __init__(self, initial_score: int):

self.my_score = initial_score

@st.cache_data(hash_funcs={"__main__.MyCustomClass": lambda x: hash(x.my_score)})

def multiply_score(self, multiplier: int) -> int:

return self.my_score * multiplier

initial_score = st.number_input("Enter initial score", value=15)

score = MyCustomClass(initial_score)

multiplier = 2

st.write(score.multiply_score(multiplier))

Above, the hash function is defined as lambda x: hash(x.my_score). This creates a hash based on the my_score attribute of the MyCustomClass instance. As long as my_score remains the same, the hash remains the same. Thus, the result of multiply_score can be retrieved from the cache without recomputation.

As an astute Pythonista, you may have been tempted to use Python's id() function to hash the object like so:

import streamlit as st

class MyCustomClass:

def __init__(self, initial_score: int):

self.my_score = initial_score

@st.cache_data(hash_funcs={"__main__.MyCustomClass": id})

def multiply_score(self, multiplier: int) -> int:

return self.my_score * multiplier

initial_score = st.number_input("Enter initial score", value=15)

score = MyCustomClass(initial_score)

multiplier = 2

st.write(score.multiply_score(multiplier))

If you run the app, you'll notice that Streamlit recomputes multiply_score each time even if my_score hasn't changed! Puzzled? In Python, id() returns the identity of an object, which is unique and constant for the object during its lifetime. This means that even if the my_score value is the same between two instances of MyCustomClass, id() will return different values for these two instances, leading to different hash values. As a result, Streamlit considers these two different instances as needing separate cached values, thus it recomputes the multiply_score each time even if my_score hasn't changed.

This is why we discourage using it as hash func, and instead encourage functions that return deterministic, true hash values. That said, if you know what you're doing, you can use id() as a hash function. Just be aware of the consequences. For example, id is often the correct hash func when you're passing the result of an @st.cache_resource function as the input param to another cached function. There's a whole class of object types that aren’t otherwise hashable.

Example 2: Hashing a Pydantic model

Let's consider another example where we want to hash a Pydantic model:

import streamlit as st

from pydantic import BaseModel

class Person(BaseModel):

name: str

@st.cache_data

def identity(person: Person):

return person

person = identity(Person(name="Lee"))

st.write(f"The person is {person.name}")

Above, we define a custom class Person using Pydantic's BaseModel with a single attribute name. We also define an identity function which accepts an instance of Person as an arg and returns it without modification. This function is intended to cache the result, therefore, if called multiple times with the same Person instance, it won't recompute but return the cached instance.

If you run the app, however, you'll run into a UnhashableParamError: Cannot hash argument 'person' (of type __main__.Person) in 'identity'. error. This is because Streamlit does not know how to hash the Person class. To fix this, we can use the hash_funcs kwarg to tell Streamlit how to hash Person.

In the version below, we define a custom hash function hash_func that takes the Person instance as input and returns the name attribute. We want the name to be the unique identifier of the object, so we can use it to deterministically hash the object:

import streamlit as st

from pydantic import BaseModel

class Person(BaseModel):

name: str

@st.cache_data(hash_funcs={Person: lambda p: p.name})

def identity(person: Person):

return person

person = identity(Person(name="Lee"))

st.write(f"The person is {person.name}")

Example 3: Hashing a ML model

There may be cases where you want to pass your favorite machine learning model to a cached function. For example, let's say you want to pass a TensorFlow model to a cached function, based on what model the user selects in the app. You might try something like this:

import streamlit as st

import tensorflow as tf

@st.cache_resource

def load_base_model(option):

if option == 1:

return tf.keras.applications.ResNet50(include_top=False, weights="imagenet")

else:

return tf.keras.applications.MobileNetV2(include_top=False, weights="imagenet")

@st.cache_resource

def load_layers(base_model):

return [layer.name for layer in base_model.layers]

option = st.radio("Model 1 or 2", [1, 2])

base_model = load_base_model(option)

layers = load_layers(base_model)

st.write(layers)

In the above app, the user can select one of two models. Based on the selection, the app loads the corresponding model and passes it to load_layers. This function then returns the names of the layers in the model. If you run the app, you'll see that Streamlit raises a UnhashableParamError since it cannot hash the argument 'base_model' (of type keras.engine.functional.Functional) in 'load_layers'.

If you disable hashing for base_model by prepending an underscore to its name, you'll observe that regardless of which base model is chosen, the layers displayed are same. This subtle bug is due to the fact that the load_layers function is not re-run when the base model changes. This is because Streamlit does not hash the base_model argument, so it does not know that the function needs to be re-run when the base model changes.

To fix this, we can use the hash_funcs kwarg to tell Streamlit how to hash the base_model argument. In the version below, we define a custom hash function hash_func: Functional: lambda x: x.name. Our choice of hash func is informed by our knowledge that the name attribute of a Functional object or model uniquely identifies it. As long as the name attribute remains the same, the hash remains the same. Thus, the result of load_layers can be retrieved from the cache without recomputation.

import streamlit as st

import tensorflow as tf

from keras.engine.functional import Functional

@st.cache_resource

def load_base_model(option):

if option == 1:

return tf.keras.applications.ResNet50(include_top=False, weights="imagenet")

else:

return tf.keras.applications.MobileNetV2(include_top=False, weights="imagenet")

@st.cache_resource(hash_funcs={Functional: lambda x: x.name})

def load_layers(base_model):

return [layer.name for layer in base_model.layers]

option = st.radio("Model 1 or 2", [1, 2])

base_model = load_base_model(option)

layers = load_layers(base_model)

st.write(layers)

In the above case, we could also have used hash_funcs={Functional: id} as the hash function. This is because id is often the correct hash func when you're passing the result of an @st.cache_resource function as the input param to another cached function.

Example 4: Overriding Streamlit's default hashing mechanism

Let's consider another example where we want to override Streamlit's default hashing mechanism for a pytz-localized datetime object:

from datetime import datetime

import pytz

import streamlit as st

tz = pytz.timezone("Europe/Berlin")

@st.cache_data

def load_data(dt):

return dt

now = datetime.now()

st.text(load_data(dt=now))

now_tz = tz.localize(datetime.now())

st.text(load_data(dt=now_tz))

It may be surprising to see that although now and now_tz are of the same <class 'datetime.datetime'> type, Streamlit does not how to hash now_tz and raises a UnhashableParamError. In this case, we can override Streamlit's default hashing mechanism for datetime objects by passing a custom hash function to the hash_funcs kwarg:

from datetime import datetime

import pytz

import streamlit as st

tz = pytz.timezone("Europe/Berlin")

@st.cache_data(hash_funcs={datetime: lambda x: x.strftime("%a %d %b %Y, %I:%M%p")})

def load_data(dt):

return dt

now = datetime.now()

st.text(load_data(dt=now))

now_tz = tz.localize(datetime.now())

st.text(load_data(dt=now_tz))

Let's now consider a case where we want to override Streamlit's default hashing mechanism for NumPy arrays. While Streamlit natively hashes Pandas and NumPy objects, there may be cases where you want to override Streamlit's default hashing mechanism for these objects.

For example, let's say we create a cache-decorated show_data function that accepts a NumPy array and returns it without modification. In the bellow app, data = df["str"].unique() (which is a NumPy array) is passed to the show_data function.

import time

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import streamlit as st

@st.cache_data

def get_data():

df = pd.DataFrame({"num": [112, 112, 2, 3], "str": ["be", "a", "be", "c"]})

return df

@st.cache_data

def show_data(data):

time.sleep(2) # This makes the function take 2s to run

return data

df = get_data()

data = df["str"].unique()

st.dataframe(show_data(data))

st.button("Re-run")

Since data is always the same, we expect the show_data function to return the cached value. However, if you run the app, and click the Re-run button, you'll notice that the show_data function is re-run each time. We can assume this behavior is a consequence of Streamlit's default hashing mechanism for NumPy arrays.

To work around this, let's define a custom hash function hash_func that takes a NumPy array as input and returns a string representation of the array:

import time

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import streamlit as st

@st.cache_data

def get_data():

df = pd.DataFrame({"num": [112, 112, 2, 3], "str": ["be", "a", "be", "c"]})

return df

@st.cache_data(hash_funcs={np.ndarray: str})

def show_data(data):

time.sleep(2) # This makes the function take 2s to run

return data

df = get_data()

data = df["str"].unique()

st.dataframe(show_data(data))

st.button("Re-run")

Now if you run the app, and click the Re-run button, you'll notice that the show_data function is no longer re-run each time. It's important to note here that our choice of hash function was very naive and not necessarily the best choice. For example, if the NumPy array is large, converting it to a string representation may be expensive. In such cases, it is up to you as the developer to define what a good hash function is for your use case.

Static elements

Since version 1.16.0, cached functions can contain Streamlit commands! For example, you can do this:

@st.cache_data

def get_api_data():

data = api.get(...)

st.success("Fetched data from API!") # 👈 Show a success message

return data

As we know, Streamlit only runs this function if it hasn't been cached before. On this first run, the st.success message will appear in the app. But what happens on subsequent runs? It still shows up! Streamlit realizes that there is an st. command inside the cached function, saves it during the first run, and replays it on subsequent runs. Replaying static elements works for both caching decorators.

You can also use this functionality to cache entire parts of your UI:

@st.cache_data

def show_data():

st.header("Data analysis")

data = api.get(...)

st.success("Fetched data from API!")

st.write("Here is a plot of the data:")

st.line_chart(data)

st.write("And here is the raw data:")

st.dataframe(data)

Input widgets

You can also use interactive input widgets like st.slider or st.text_input in cached functions. Widget replay is an experimental feature at the moment. To enable it, you need to set the experimental_allow_widgets parameter:

@st.cache_data(experimental_allow_widgets=True) # 👈 Set the parameter

def get_data():

num_rows = st.slider("Number of rows to get") # 👈 Add a slider

data = api.get(..., num_rows)

return data

Streamlit treats the slider like an additional input parameter to the cached function. If you change the slider position, Streamlit will see if it has already cached the function for this slider value. If yes, it will return the cached value. If not, it will rerun the function using the new slider value.

Using widgets in cached functions is extremely powerful because it lets you cache entire parts of your app. But it can be dangerous! Since Streamlit treats the widget value as an additional input parameter, it can easily lead to excessive memory usage. Imagine your cached function has five sliders and returns a 100 MB DataFrame. Then we'll add 100 MB to the cache for every permutation of these five slider values – even if the sliders do not influence the returned data! These additions can make your cache explode very quickly. Please be aware of this limitation if you use widgets in cached functions. We recommend using this feature only for isolated parts of your UI where the widgets directly influence the cached return value.

Warning

Support for widgets in cached functions is experimental. We may change or remove it anytime without warning. Please use it with care!

Note

Two widgets are currently not supported in cached functions: st.file_uploader and st.camera_input. We may support them in the future. Feel free to open a GitHub issue if you need them!

Dealing with large data

As we explained, you should cache data objects with st.cache_data. But this can be slow for extremely large data, e.g., DataFrames or arrays with >100 million rows. That's because of the copying behavior of st.cache_data: on the first run, it serializes the return value to bytes and deserializes it on subsequent runs. Both operations take time.

If you're dealing with extremely large data, it can make sense to use st.cache_resource instead. It does not create a copy of the return value via serialization/deserialization and is almost instant. But watch out: any mutation to the function's return value (such as dropping a column from a DataFrame or setting a value in an array) directly manipulates the object in the cache. You must ensure this doesn't corrupt your data or lead to crashes. See the section on Mutation and concurrency issues below.

When benchmarking st.cache_data on pandas DataFrames with four columns, we found that it becomes slow when going beyond 100 million rows. The table shows runtimes for both caching decorators at different numbers of rows (all with four columns):

| 10M rows | 50M rows | 100M rows | 200M rows | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| st.cache_data | First run* | 0.4 s | 3 s | 14 s | 28 s |

| Subsequent runs | 0.2 s | 1 s | 2 s | 7 s | |

| st.cache_resource | First run* | 0.01 s | 0.1 s | 0.2 s | 1 s |

| Subsequent runs | 0 s | 0 s | 0 s | 0 s |

| *For the first run, the table only shows the overhead time of using the caching decorator. It does not include the runtime of the cached function itself. |

Mutation and concurrency issues

In the sections above, we talked a lot about issues when mutating return objects of cached functions. This topic is complicated! But it's central to understanding the behavior differences between st.cache_data and st.cache_resource. So let's dive in a bit deeper.

First, we should clearly define what we mean by mutations and concurrency:

-

By mutations, we mean any changes made to a cached function's return value after that function has been called. I.e. something like this:

@st.cache_data def create_list(): l = [1, 2, 3] l = create_list() # 👈 Call the function l[0] = 2 # 👈 Mutate its return value -

By concurrency, we mean that multiple sessions can cause these mutations at the same time. Streamlit is a web framework that needs to handle many users and sessions connecting to an app. If two people view an app at the same time, they will both cause the Python script to rerun, which may manipulate cached return objects at the same time – concurrently.

Mutating cached return objects can be dangerous. It can lead to exceptions in your app and even corrupt your data (which can be worse than a crashed app!). Below, we'll first explain the copying behavior of st.cache_data and show how it can avoid mutation issues. Then, we'll show how concurrent mutations can lead to data corruption and how to prevent it.

Copying behavior

st.cache_data creates a copy of the cached return value each time the function is called. This avoids most mutations and concurrency issues. To understand it in detail, let's go back to the Uber ridesharing example from the section on st.cache_data above. We are making two modifications to it:

- We are using

st.cache_resourceinstead ofst.cache_data.st.cache_resourcedoes not create a copy of the cached object, so we can see what happens without the copying behavior. - After loading the data, we manipulate the returned DataFrame (in place!) by dropping the column

"Lat".

Here's the code:

@st.cache_resource # 👈 Turn off copying behavior

def load_data(url):

df = pd.read_csv(url)

return df

df = load_data("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/plotly/datasets/master/uber-rides-data1.csv")

st.dataframe(df)

df.drop(columns=['Lat'], inplace=True) # 👈 Mutate the dataframe inplace

st.button("Rerun")

Let's run it and see what happens! The first run should work fine. But in the second run, you see an exception: KeyError: "['Lat'] not found in axis". Why is that happening? Let's go step by step:

- On the first run, Streamlit runs

load_dataand stores the resulting DataFrame in the cache. Since we're usingst.cache_resource, it does not create a copy but stores the original DataFrame. - Then we drop the column

"Lat"from the DataFrame. Note that this is dropping the column from the original DataFrame stored in the cache. We are manipulating it! - On the second run, Streamlit returns that exact same manipulated DataFrame from the cache. It does not have the column

"Lat"anymore! So our call todf.dropresults in an exception. Pandas cannot drop a column that doesn't exist.

The copying behavior of st.cache_data prevents this kind of mutation error. Mutations can only affect a specific copy and not the underlying object in the cache. The next rerun will get its own, unmutated copy of the DataFrame. You can try it yourself, just replace st.cache_resource with st.cache_data above, and you'll see that everything works.

Because of this copying behavior, st.cache_data is the recommended way to cache data transforms and computations – anything that returns a serializable object.

Concurrency issues

Now let's look at what can happen when multiple users concurrently mutate an object in the cache. Let's say you have a function that returns a list. Again, we are using st.cache_resource to cache it so that we are not creating a copy:

@st.cache_resource

def create_list():

l = [1, 2, 3]

return l

l = create_list()

first_list_value = l[0]

l[0] = first_list_value + 1

st.write("l[0] is:", l[0])

Let's say user A runs the app. They will see the following output:

l[0] is: 2

Let's say another user, B, visits the app right after. In contrast to user A, they will see the following output:

l[0] is: 3

Now, user A reruns the app immediately after user B. They will see the following output:

l[0] is: 4

What is happening here? Why are all outputs different?

- When user A visits the app,

create_list()is called, and the list[1, 2, 3]is stored in the cache. This list is then returned to user A. The first value of the list,1, is assigned tofirst_list_value, andl[0]is changed to2. - When user B visits the app,

create_list()returns the mutated list from the cache:[2, 2, 3]. The first value of the list,2, is assigned tofirst_list_valueandl[0]is changed to3. - When user A reruns the app,

create_list()returns the mutated list again:[3, 2, 3]. The first value of the list,3, is assigned tofirst_list_value,andl[0]is changed to 4.

If you think about it, this makes sense. Users A and B use the same list object (the one stored in the cache). And since the list object is mutated, user A's change to the list object is also reflected in user B's app.

This is why you must be careful about mutating objects cached with st.cache_resource, especially when multiple users access the app concurrently. If we had used st.cache_data instead of st.cache_resource, the app would have copied the list object for each user, and the above example would have worked as expected – users A and B would have both seen:

l[0] is: 2

Note

This toy example might seem benign. But data corruption can be extremely dangerous! Imagine we had worked with the financial records of a large bank here. You surely don't want to wake up with less money on your account just because someone used the wrong caching decorator 😉

Migrating from st.cache

We introduced the caching commands described above in Streamlit 1.18.0. Before that, we had one catch-all command st.cache. Using it was often confusing, resulted in weird exceptions, and was slow. That's why we replaced st.cache with the new commands in 1.18.0 (read more in this blog post). The new commands provide a more intuitive and efficient way to cache your data and resources and are intended to replace st.cache in all new development.

If your app is still using st.cache, don't despair! Here are a few notes on migrating:

- Streamlit will show a deprecation warning if your app uses

st.cache. - We will not remove

st.cachesoon, so you don't need to worry about your 2-year-old app breaking. But we encourage you to try the new commands going forward – they will be way less annoying! - Switching code to the new commands should be easy in most cases. To decide whether to use

st.cache_dataorst.cache_resource, read Deciding which caching decorator to use. Streamlit will also recognize common use cases and show hints right in the deprecation warnings. - Most parameters from

st.cacheare also present in the new commands, with a few exceptions:allow_output_mutationdoes not exist anymore. You can safely delete it. Just make sure you use the right caching command for your use case.suppress_st_warningdoes not exist anymore. You can safely delete it. Cached functions can now contain Streamlit commands and will replay them. If you want to use widgets inside cached functions, setexperimental_allow_widgets=True. See Input widgets for an example.

If you have any questions or issues during the migration process, please contact us on the forum, and we will be happy to assist you. 🎈

Still have questions?

Our forums are full of helpful information and Streamlit experts.